Ch…Ch… Ch… Ch….Changes!

If you were going to pick an icon for the upcoming race at Kentucky, it would be a giant question mark. It’s almost like coming to a brand new track.

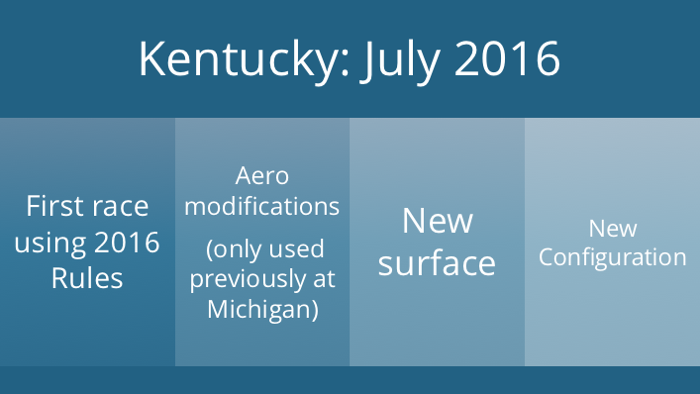

- This is the first race of the year in Kentucky, so we’re dealing with the new 2016 rules package.

- On top of the 2016 rules package, there are aerodynamic modifications being tested for 2017. They were tested at Michigan, but that’s the only experience the teams have had with them.

- The race track surface is brand new, with not only a new surface, but a different asphalt mix

- The track has changed configuration, with turns 1/2 now having 17 degrees of banking while 3/4 remain 14 degrees.

While crew chiefs are pulling out their hair this weekend, the hair-pulling process has been going on much longer for the engineers at Goodyear. They have a true challenge: While having the right tires doesn’t guarantee a great race, having the wrong tires guarantees the week’s commentary is going to be focused on Goodyear and not who won the racer.

I spent some time talking with Greg Stucker, Goodyear’s Director of Racing, about how Goodyear responds when a track decides it’s finally time to repave. Here’s something that probably doesn’t surprise long-time readers of this blog. The most important thing when it comes to track repaving isn’t coefficients of friction or tire loads.

It’s communication.

Goodyear is involved from the day the track decides they’re going to repave. It’s important for Goodyear to understand what changes are going to be made and (just as importantly) why the track wants to make those changes. Stucker called out two major issues: what the new surface is going to be like and whether there will be changes in the track’s configuration.

Sometimes, all a track does is put down a new surface without changing the configuration. But frankly, if you’re a track owner or manager, you’re going to want to take advantage of having everything dug up to make any changes you’ve been itching to make.

Bumps in the Road

The surface at Kentucky was the original surface from when the track opened in 2000. Now, Kentucky has a lot of groundwater. Their groundwater is close to the surface, which means when it freezes it becomes ground-ice.

One of the unique properties of water is that it is one of the very few substances that expands when it freezes. This means the ground constantly expands and contracts as the temperature changes. The ground exerts a forces on the asphalt, but asphalt isn’t as malleable as dirt. Instead of shifting or deforming, it cracks. This produced a number of larger bumps that caused drivers to liken the surface to “a washboard”.

“it’s like running over a freeway that truck drivers have been on and (the road crews) have tried to patch in some spots where (the trucks) made some divots. It’s a rough trip.” — Brad Keselowski from a Lexington Herald-Leader story.

Kentucky was bumps from the middle of turns 3 and 4 all the way down the frontstretch and into turns 1 and 2. Teams had to modify their setups specifically to accommodate the bumps.

Now, if you run a racetrack, you really don’t want the thing that defines your track to be “bumps”. The groundwater caused some other problems as well. When it rained, the track had to deal with really bad weepers that delayed track drying efforts. The re-pave was an opportunity to deal with the drainage issues.

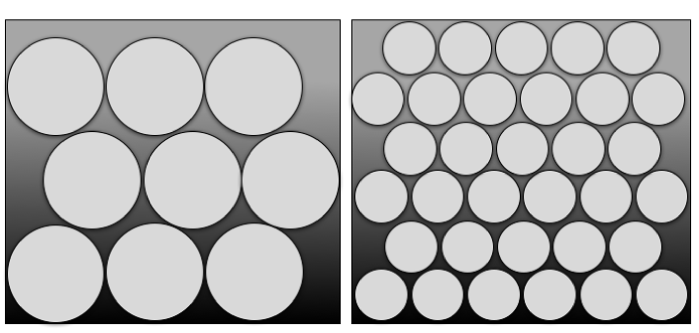

The solution is to make the asphalt mix more porous. That’s accomplished by using larger aggregate (aka “rocks”) in the asphalt mix. Believe it or not, the size distribution of the aggregate has a pretty significant effect on the way the track wears.

I’ve shown two samples of asphalt with two aggregate sizes above. (Yes, I made them round because I didn’t want to take the time to draw gravel-shaped gravel.) I tried to pack as many circles as I could in each square of asphalt.

Notice how much binder (the black stuff that represents the gooey black tar-like substance that holds the rocks together) there is for each case. The smaller the aggregate, the less binder there is. Smaller pieces fill nooks and crannies and decrease the fraction of the track that is binder compared with the fraction that is rock.

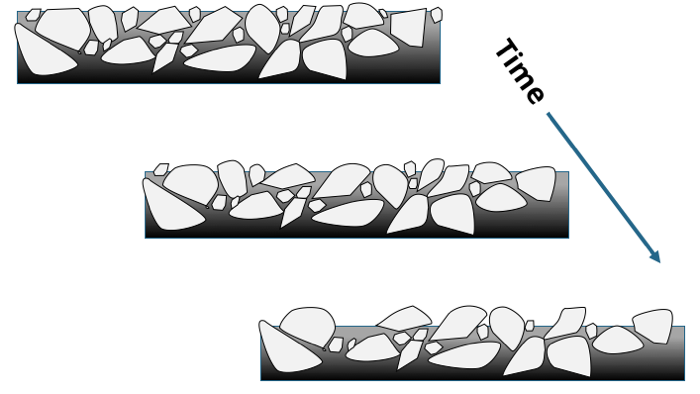

Why is this important? Because when we talk about wear, what we’re really talking about is the binder. Sure, the rocks will smooth out a little bit over time, but its mostly the erosion of the binder, as I’ve shown below.

This means that the track surface will age faster than if they had used smaller aggregate and (hopefully) will solve some of the drainage problems they’ve experiences in the past.

Tracking Uniqueness

I’m pretty sure everyone who runs a 1.5 mile track winces when they hear the word ‘cookie cutter’. People who are paying attention know that’s a specious charge at best, but it gets repeated enough that people believe it.

So if you’re going to go to all the trouble of digging up the track, why not do something different? Why not do something to distinguish your track from all the other 1.5 mile tracks?

Like put different banking in the different corners. The new Kentucky now has 17° of banking in turns 1 and 2, while turns 3 and 4 retain the original 14° . You might think this is just a way to mess with the crew chiefs because they have to pick which set of turns to optimize the setup in.

Yes, that is going to happen, but there’s even more to it than that.

Drivers have long commented that the entry to turn 3 is tricky. So the folks at Kentucky figured — why not make it even trickier. Increased banking means increased speed. If going into turn 3 at 180 mph is tricky, imagine how it will be when it’s five mph faster.

Developing a New Tire for a New Track

I analyzed the aerodynamic changes in the rules that were implemented last month at Michigan previously. Everyone got a little experience with those at Michigan and people felt pretty good about the changes. This week, Goodyear has to take the new aerodynamics into consideration plus the new track configuration and surface.

Kentucky Speedway announced their intention to repave on January 5th of this year. It was definitely needed — but that left Goodyear no time to run a tire test before the July race.

I know — you’re thinking “They did a tire test last month, right after Michigan, didn’t they? More on that in a moment.

The Big Picture

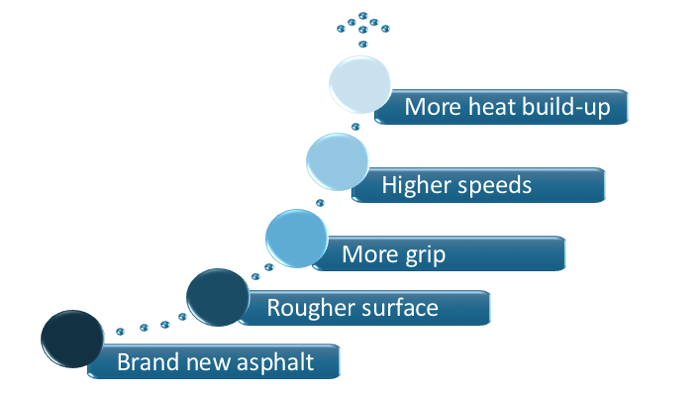

There are some things you know for sure will happen. For example, increased banking produces increased speeds and higher loads on tires. A new surface is not only grippier, it tends to have less wear, which means you get more heat build up in the tires.

The amount of change isn’t something they can predict ahead of time, but past experience gives Goodyear a pretty good baseline from which to work.

Getting Data Before the Track is Finished

Lab Tests: Goodyear gets “pours samples” from the company handling the re-paving. These are small pieces of the surface, laid under similar conditions, that allow Goodyear to run tests on hardness, friction, durability/wear and other parameters that will help them predict how a specific tire compound and construction will interact with the track in terms of grip, heat dissipation and wear.

Computer Simulations: Goodyear leverages all the work NASCAR teams have done in developing vehicle dynamics simulations by asking the teams to share their predictions about what tire loads they expect from the new conditions. Since the teams have to deal with the whole car (aero, dynamics, etc.) they have a unique, holistic view of what to expect.

It’s in the teams’ best interests to have the best tire they can get, so they are open about their concerns as to how they might have to change their setups with the new situation. NASCAR also contributes the information they gather on what to expect from any changes to a track.

With teams relying more and more on computer simulations, I asked Greg whether Goodyear used simulation programs. Perhaps they had developed a program where they could type in the specifics of the binder, the aggregate mix, etc. and predict how the surface would behave. Greg sort of laughed and told me they are “not quite there yet”.

Similarities to Existing Tracks: If all 1.5-mile tracks were truly identical, picking a tire wouldn’t be hard at all.

But they’re not, so Goodyear looked at all the other tracks. As I’ve discussed before, Goodyear makes ‘Venue Groupings’. For example, Bristol, Indy, Iowa, Phoenix and Pocono are in one grouping, even though they are very different shaped and sized tracks. The loads the tires experience, the speeds and the wear rates are the important parameters here.

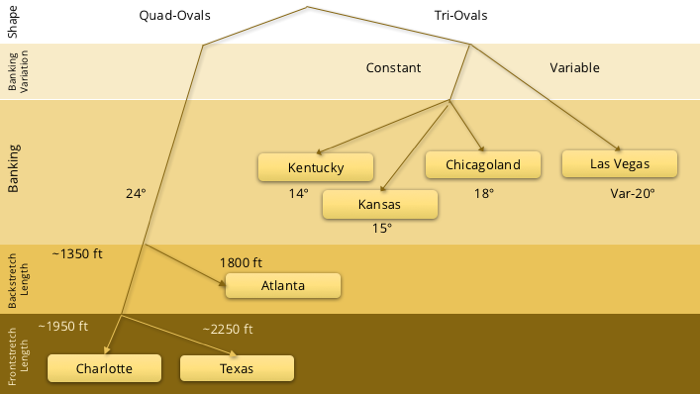

All of the 1.5-mile tracks fall in one of two venue groupings (which also include Darlington, Michigan, Dover and California). In my effort to dispel the notion that the 1.5-mile tracks are cookie cutters, I had previously made a diagram to categorize the 1.5 mile tracks. Here’s the way it looked in 2012 (note that I cleaned it up and left off Homestead, which is a true oval with variable banking to make it a little easier to read.

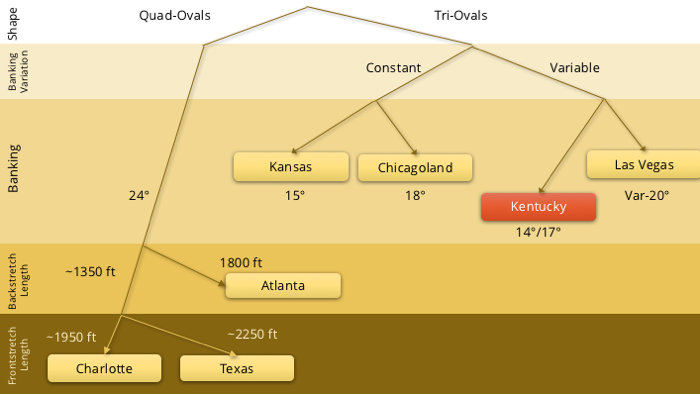

So if all they had done was repave and you were looking for comparable tracks, you’d probably try a tire from Kansas or Chicago, or maybe even Atlanta. But since Kentucky is now repaved and re-configured, I had to change my chart.

And I still left Homestead off. Sorry, Homestead.

Note which track Kentucky now seems most like. Las Vegas, maybe? Keep that in the back of your mind for a couple more paragraphs.

Premature Aging

While most of us struggle to hold onto our youth, new tracks wish they were old.

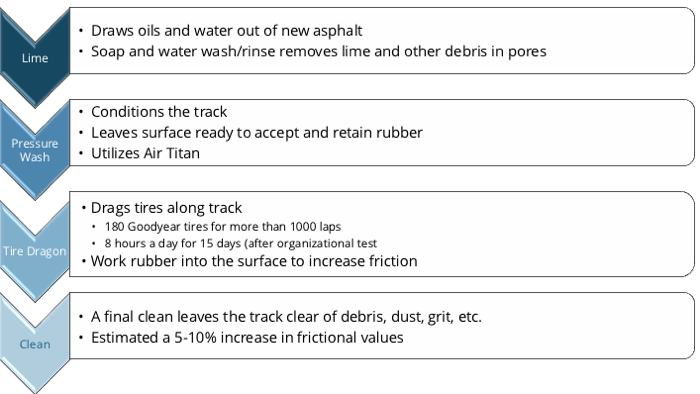

No one likes a brand spanking-new racetrack. They’re so smooth and grippy, some fans (and some drivers) complain they’re too easy to drive. To try to avoid NTS (New Track Syndrome), Kentucky has accelerated the track aging process. When I was talking to Greg, I used the analogy of buying pre-distressed jeans. No one likes the stiff, uniformly blue feel of brand-new jeans, so the companies wash them with rocks or bleach them or do other things to make them feel already lived-in.

That’s what they’ve done to the Kentucky Speedway.

And don’t forget that the larger aggregate mix make it easier to accelerate the aging process. (NOTE: I’ve heard 200 tires and I’ve heard 130. Either way, it was a bunch.)

The Tire Dragon is an interesting instrument that bears a paragraph of its own. Using tires on a track is nothing new, but it’s often done either by having drivers runs laps, or by dragging tires that are usually chained behind a pickup.

Neither one of those methods is very efficient. Dragging is much better than driving because the tires aren’t rotating and more rubber will be removed; however, the rubber you want on the track is the tread rubber, not the rubber from the sidewall. The picture below is from Kansas and the important thing to know is that the four tires on the back of the tractor aren’t just rolling along. In fact, they’re rotating in the opposite direction as the wheels of the tractor and being pressed into the track to maximize the transfer of rubber..

So it’s not really “dragon”, right? But dragon sounds so much cooler, so we’ll just go with that. If you look on the back, they even have a logo for it.

Boldly Going Where No Tire Has Gone

When I spoke with Mike Siberini, Goodyear’s Media Relations Manager, he corrected me when I referred to the June 13th-14th run at Kentucky as a ‘tire test’. It was actually an organizational test. Here’s the difference:

In a tire test: Goodyear rents the track and chooses the teams to participate. There are four teams (all manufacturers are represented) and Goodyear dictates the setups, lengths of runs, etc. They usually bring a number of different tires with the intention of comparing behavior and thus want similar circumstances (set up, speed, run length) to make the comparison more accurate.

In an organizational test: Each company is invited to send one team (i.e. no matter how many cars your company runs, you get to send one). Each company decides who to send. NASCAR rents the track. The teams make their own decisions as to what they want to test. Goodyear provides tires.

The test in June was an organizational test. Goodyear knew that the short time between the completion of the track and the race wouldn’t allow them to do a true tire test, especially since NASCAR wanted the teams to have time to work with the new aerodynamics package.

Goodyear decided to bring one tire to the organizational test and see how it fared.

They looked at all the data they had and through all their past experience and brought the same tires used in Las Vegas. (Go look at my chart again. See? And yes, I made the chart before I talked to Greg and learned this!) The Las Vegas tire was a conservative choice, but given the time and logistical considerations, that’s the way Goodyear has to go.

So what happened? Greg told me everything went pretty much the way they predicted during the test… until the second half of the second day. At that point, they started see blistering on the right sides after long (20–25 laps) runs.

Greg didn’t say this, but I can pretty much guess what happened. At the start of the test, teams played it safe as they tried to figure out the new track and the aerodynamic changes. The longer the teams experimented, the better they were able to tune their setups — and the more aggressive they were willing to be. Speeds increased. One of the problems with a grippy new track is that there isn’t as much wear and wear is one way to reduce heat buildup in the tires. The more speed, the more heat. The less wear, the more heat.

By the afternoon of the second day, the teams had found the upper limit for the right-side tires.

So — with three weeks left before they needed to send tires to Kentucky for this weekend’s race — Goodyear decided against using the Las Vegas right-side tires. They built 1300 brand new right-side tires, with the same construction as the Vegas tire, but without the multi-zone tread.

NASCAR race tires are hand-made, so I’ll just repeat: 1300 right-side tires in three weeks.

So Now It’s Just the Race, Right?

With the tire selected, you might think all the Goodyear team will do it bite their fingernails until racetime when they see if their process paid off.

No! Greg tells me that the most important part of this weekend for Goodyear are the practice sessions because they are the closest thing to the actual race. Goodyear engineers monitor tires in great detail during practices. They’ll get tire pressure readings from the teams’ tire specialists, and Goodyear Engineers take tire temperatures themselves (at three places across the tire). Since temperature increases with tire load, that data gives Goodyear a really good real-time understanding of how the tires are behaving during race-like activity. They’ll also solicit feedback from drivers and crew chiefs.

I hesitated to ask Greg what happens if the data they get from practice sessions suggests they didn’t make the right choice. But I did. He assured me that Goodyear has a contingency plan in place. He didn’t tell me what it was, but he did say they also had a contingency plan for their contingency plan. When you’ve got a hundred thousand people there and millions watching, contingency plans are the order of the day.

Pre-Scuffing Tires

Goodyear does monitor every team individually. If one team is having problems and others aren’t, someone from Goodyear will take the crew chief aside and tell them that they need to cut back on the camber or otherwise back off how aggressive their setup is. Teams are under no compunction to do as they are advised, but when the people who designed and made the tire tell you you’re doing something wrong, you’d have to be pretty dense not to pay attention.

One thing they are advising the teams is to go ahead and scuff tires during practice. Rubber is a polymer — a long, long chain of atoms linked together. As the tire temperature increases and they are subject to mechanical friction, bonds between the atoms stretch and break. If the first run on the track places a lot of stress on the tires, some of the stronger bonds in the tires could be broken. That reduces the tire’s grip and increases its wear.

When a tire is made, there are areas of high stress, where the molecular bonds are already stretched. Running a few laps at moderate speeds (i.e. enough to heat them up, but not to the maximum race temperate) on a brand new breaks those bonds. Over the next 24–48 hours, the tires sit and the bonds re-form. Since the tires have been heated and the highly stressed regions broken up, they re-form stronger and more uniformly. The cords and the tread settle and you’ve got a more durable tire that’s less likely to blow out.

Many thanks to Mike Siberini and Greg Stucker for taking the time to talk with me about how much work went into making the tires for this week’s race.

Please help me publish my next book!

The Physics of NASCAR is 15 years old. One component in getting a book deal is a healthy subscriber list. I promise not to send more than two emails per month and will never sell your information to anyone.

Discover more from Building Speed

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Be the first to comment