This was the first year that most people noticed a decrease in the number of cautions, but (as I’ve pointed out), 2012 is merely the latest in a six-year trend of decreasing cautions. The same downward trend is evident in the Nationwide Series. This year is perhaps notable for it being so extreme.

I’ve plotted the cautions per 100 miles (the best way I’ve found to compare changing race lengths and different tracks) for Cup races so far this year at right. The plot shows the minimum and maximum values for each track, with the average shown by an open square. The red square shows the cautions for 2012. At California, Bristol, Martinsville, Texas, Kansas, Talladega and Darlington, the 2012 value is the lowest value in the last six years.

I’ve plotted the cautions per 100 miles (the best way I’ve found to compare changing race lengths and different tracks) for Cup races so far this year at right. The plot shows the minimum and maximum values for each track, with the average shown by an open square. The red square shows the cautions for 2012. At California, Bristol, Martinsville, Texas, Kansas, Talladega and Darlington, the 2012 value is the lowest value in the last six years.

The data clearly shows the trend: The question, of course, is why?

Given that it’s happening in both Nationwide and Cup, that sort of eliminates issues like the introduction of new cars (either COT or the new Nationwide car), the Chase Format, etc. What was left to investigate? How about the drivers? A number of commentators has suggested that drivers were just “better” now. But how do you test this?

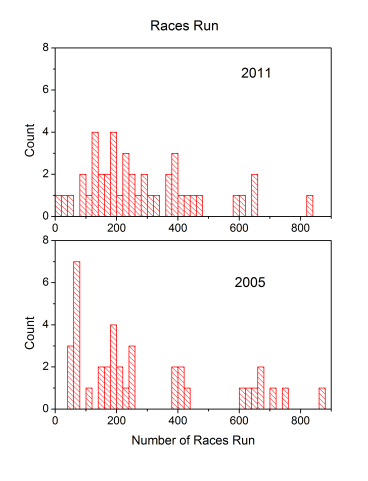

I started by deciding that experience and quality could be indicated by number of races run and number of races won, respectively. I decided to compare 2005 (which had the highest number of cautions) with 2011.

My criteria for including drivers was that the driver had to have run more than 15 races during the season. That kept the focus on the full-time drivers. I totaled two quantities for the drivers that made the cut: the total number of career laps they had run in the Cup Series (including the season in question) and the total number of career races they had won in the Cup Series.

| Year | 2005 | 2011 |

| Races run | 11109 | 12180 |

| Races won | 485 | 485 |

The drivers who spent the most time on track in 2011 had about a thousand (1071 to be precise) more races worth of experience: with roughly 25 drivers included that’s an average experience level of 40 races, or almost a full season per driver. The number of wins was exactly the same.

I looked into the details as to what had really changed between 2005 and 2011. We lost a lot of experienced drivers from active competition: Dale J arrett, Ricky Rudd, Rusty Wallace, Sterling Marlin, Kyle Petty, Michael Waltrip, and Ken Schrader for starters. Their places were taken by drivers just starting out: From 2005 to 2011, Kasey Kahne went from 72 races run and 1 win to 288 races run and 12 wins. Kyle Busch went from 42 races and 2 wins in 2005 to 257 races and 23 wins in 2011. Jamie McMurray didn’t make the active list in 2005, but in 2011 had 230 races and 6 wins. Even the folks we think of as veterans, look at Tony Stewart: from 248/24 to 464/44, and Carl Edwards: 49/4 to 265/19.

arrett, Ricky Rudd, Rusty Wallace, Sterling Marlin, Kyle Petty, Michael Waltrip, and Ken Schrader for starters. Their places were taken by drivers just starting out: From 2005 to 2011, Kasey Kahne went from 72 races run and 1 win to 288 races run and 12 wins. Kyle Busch went from 42 races and 2 wins in 2005 to 257 races and 23 wins in 2011. Jamie McMurray didn’t make the active list in 2005, but in 2011 had 230 races and 6 wins. Even the folks we think of as veterans, look at Tony Stewart: from 248/24 to 464/44, and Carl Edwards: 49/4 to 265/19.

Even drivers who haven’t won races have run a lot more races and gained a lot more experience: Dave Blaney (200 races by 2005 vs. 397 races by 2011).

So I started thinking about the average experience of the drivers. I made histograms of the number of drivers who had run some number of races, as shown at right and below. They are plotted on the same vertical scale for easy comparison.

In 2005, 10 drivers had under 100 races worth of experience. In 2011, only 5 drivers had 100 races or less on their resumes. (One of those five was the 2011 Daytona 500 winner.) In 2005, 27% of the drivers had fewer than 100 races under their belts, while in 2011, the figure was only 12%. Yes, we lost a lot of really experienced driver with more than 600 races under their belts, but the younger, newer drivers also gained a lot of experience over those five years.

There were plenty of people making the aggrandized claim that the reason cautions are decreasing is “these are the best race car drivers in the world”. I’d make a slightly less aggressive conclusion and say that NASCAR has much more experienced drivers now than they had in 2005 and that’s why the number of cautions has decreased.

There are (as always) caveats. Having watched the Nationwide race at Charlotte and poor Travis Pastrana causing multiple cautions, it would be interesting to go back and look at whether the drivers I didn’t count in this survey had more wrecks than the regular drivers.

Please help me publish my next book!

The Physics of NASCAR is 15 years old. One component in getting a book deal is a healthy subscriber list. I promise not to send more than two emails per month and will never sell your information to anyone.

Discover more from Building Speed

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Travis was having a race like David Ragan did a few years ago at Bristol. Tony Stewart called Ragan a dart without feathers.

I remember Kyle Busch crashing in a lot of the earlier races while showing great speed. And the TV commentators were saying that when he learned how to finish the races, he’d be a factor.

Carl Edwards used to be involved in a lot more crashes. Even ole “5 time”.

Diandra, your theory seems to fit well.

Perhaps NASCAR needs to look for ways to decrease expenses. The way the economy is right now, nobody can afford to start a race team. Large teams like Hendrick aren’t going to take a chance on a driver that they aren’t sure about. I also think todays drivers are a little too “soft”.

How about $.$$ data input into your reduced cautions study?

Could the owners be profiting or just staying in business because — “less cautions” impact their bottom line.

Mega thousands of dollars to repair costs one of these sheet metal works of art.

Reduced TV time and sponsor plugs.

Less purse and points $$$$$.$$

All other expenses related to stuffing it in the wall.

Reprocussions from other owners who’s cars were involved and must deal with all the above.

Driver repeat offenders losing their big dollar dream job.

Water bottle toss out the window could lead to a mega mess (Expense) on the restart.

Just trying to look outside the box.